Every day, through multiple mediums, we see advertisements. It’s estimated that we’re exposed to between 6.000 and 10,000 ads every single day.

Most of us tune them out, but if you stop and look at the psychological strategies used in advertising, things get interesting. Marketers wouldn’t keep using ads if they didn’t work. So, what is it about them that makes people buy?

Here we’ll look into the persuasive techniques in advertising commonly used to get people to invest in a product. We’ll begin by breaking down the concept at the heart of so many advertisements: the logical triangle.

The logical triangle and its relation to persuasive techniques in advertising

2,000 years ago, in the Rhetoric, Aristotle detailed the three modes of persuasive argument: ethos, logos, and pathos. He argued that persuasion always contains at least one of these rhetorical elements, and people still rely on them today — including advertisers.

Modern technology makes it even easier to learn what persuades people. Online browsing and shopping data can show what someone’s preferences are and what they’re likely to do next without having to speak to them.

Advertisers can make persuasive, digital arguments right on our laptops and phone screens based on that data. Targeted browsing ads are a perfect example of this, using what people have already displayed an interest in to market a product.

The three modes of argument can be summarized like this:

- Ethos: Appeals to the audience based on the ethics or character of the speaker

- Pathos: Appeals to the audience’s emotions

- Logos: Appeals to the audience’s sense of logic by arguing with hard facts

You probably already have an idea of how each of these is used in advertising. Let’s break them down further, starting with ethos.

Ethos

Ethos highlights the credibility or authority of the speaker, hoping to persuade the audience through that authority. Advertisers leverage this by trying to instill their brand with a sense of credibility, thereby building trust with the audience.

The easiest way to do that is to bring in someone the audience already knows and respects. The idea is that, by endorsing a product or service, the speaker lends their credibility to it.

Celebrity endorsements are how we usually see this happen. Remember Shaq’s Icy Hot ads? They were cheesy, but they probably sold a lot. And of course, advertisers have gotten a lot savvier since then.

Take Ryan Reynolds’ ads. The YouTube spots for his mobile company Mint or alcohol company Aviation Gin are short, funny, and consistently self-deprecating. They poke fun at the very idea of celebrity endorsement.

But, we still know and love Reynolds, so it works. And, he has the connections to bring in other beloved celebrities like LeVar Burton to play along.

Ethos arguments go deeper than celebrity endorsement, though. They also speak to the fundamental character of something, relying on the ethics of an ideal to sell a product.

Anheuser-Busch’s 2017 Super Bowl ad, entitled “Born The Hard Way,” is a perfect example of this type of ethos-driven argument. The minute-long ad follows one of the company’s founders as he immigrates to America from Germany with a dream: to brew beer.

He gets knocked around, derided, and discouraged, but he doesn’t give up. In the end, he meets the other founder of Anheuser-Busch in a bar, and history is made. By telling that story, the company connects the noble ideal of the American dream to their beer and imbues the company as a whole with that work ethic.

One final example of ethos at work is the “plain folks” argument. In this type of persuasion, the speaker makes themself appear as an everyman, a “regular joe” that’s just like you. This aligns the values of their brand with those of everyday people in an attempt to make the speaker more relatable.

Politicians use this kind of advertising a lot to paint themselves as on the side of the common person. They present themselves as regular people to seem more relatable and to shed the “Washington elite” stereotype.

The “plain folks” appeal, however, is a logical fallacy, implying that the speaker is of the same social class as the audience. Persuasive techniques in advertising play on the audience’s existing beliefs the same way propaganda does. We’ll see more examples of that in the other forms of argument.

Pathos

Instead of relying on the character of the speaker as an ethos argument would, pathos is all about the heartstrings.

Whether it’s a print ad or a well-produced commercial, emotion can be incredibly effective when it comes to selling a product. If you can elicit an emotion in someone, they tend to connect that emotion with the product being sold, which compels them to take action on that emotion by buying it.

According to Psychology Today, people evaluate brands largely based on emotion, not logic. And they ascribe personality traits to brands in the same way as other people. Brands that trigger a strong emotional response are perceived as attractive and valuable.

Advertisers have mastered the art of triggering a strong emotional response in just a few seconds. A cute puppy, a heartfelt story of triumph, or a physically attractive person can all cause a strong response in us that gets connected to that product.

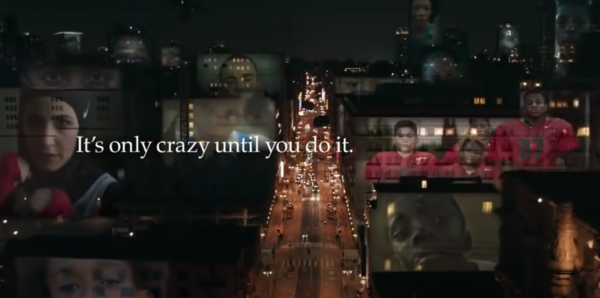

Take Nike’s “Just Do It” ad with Colin Kaepernick as an example. In 2018, Nike made the quarterback turned activist the centerpiece of an ad campaign centered around the message of standing up for what you believe in.

This was fitting, as it was shortly after Kaepernick became a nationally divisive figure by taking a knee during the U.S. national anthem in protest of police brutality.

In the Nike spot, Kaepernick narrates over images of athletes not usually seen in white-dominated media: a Black skateboarder, a Muslim woman wearing a head covering (branded with the Nike swoosh), and an NFL player with one hand. An understated, poignant piano track underscores it all.

“So don’t ask if your dreams are crazy,” Kaepernick says at the end of the ad. “Ask if they’re crazy enough.” The words, “It’s only crazy until you do it,” come on screen simultaneously as a reference to his activism and the ad’s message.

The ad feels gritty and documentary-style. It’s designed to feel like an underdog story — resilient and tough. And that’s exactly how Nike wants the viewer to see their brand: tough, athletic, and backing the underdog.

It doesn’t always have to be a happy or a sad emotion, as long as the response can be related to the message or product in some way. An anti-drunk driving ad might tell the story of someone who has to live with the guilt of a devastating accident to drive its message home. A soft drink ad might rely on peppy music, smiling actors, and bright colors to convey a feeling of happiness and optimism.

Some common logical fallacies that get leveraged often in pathos-based arguments and ads are the bandwagon concept, “snob appeal,” and patriotism. All of these will get a rise out of people for different reasons.

The bandwagon effect is pretty self-explanatory — it’s the “everybody’s doing it” argument. It plays on the fear of missing out on something great by not doing the thing (or using the product) that everyone else is. Getting the product, on the other hand, puts you in the in-group.

One funny example of the bandwagon effect is Old Spice’s “Man Your Man Could Smell Like” ads. The suave, shirtless spokesman tells the viewer that their man could smell like him if he “stopped using lady-scented body wash” before being magically transported to a boat, and then a horse.

“Snob appeal” is another popular form of pathos-based persuasion, and it’s the complete opposite of the “plain folks” appeal. Advertisers use their product as a status signifier, a way to broadcast that those who have it are better than others.

Almost every luxury brand leans heavily into this kind of selling. “You’re too good for an ordinary car,” says BMW, “You need the Ultimate Driving Machine.”

Logos

Also called “the logic appeal,” logos-based arguments use logic, reason, and fact to appeal to the audience. You’ll know an ad is using a logos argument if it relies heavily on charts, stats, and data to appeal to the viewer.

Apple, of course, does this brilliantly with every iteration of its products. The iPhone, in particular, is marketed as a borderline magic device but the ads never neglect the tech specs. The newest spot for the iPhone 12 touts its night mode camera and A14 processor chip in snappy, well-produced shots.

By appealing to logic, logos-based advertising appears to remove any sense of subjective bias. It presents the facts. And, if those facts happen to paint the product as amazing, well then it must just be amazing.

You’ll see ads for tech products use logos arguments often because it’s easy to tick off a list of amazing product specs. Innovative features are used as reasons you should buy the product. Crack-resistant glass, amazing camera images, and a faster processor all sound like good reasons to upgrade your phone.

And it isn’t just tech ads using logic to sell. As long as you have facts to present that make your product seem superior, you can make a logos-based argument. Food advertisements do this all the time, using language like “organic”, “plant-based”, or “non-GMO” to present their brand as a healthy alternative to the competition.

Medical ads also go this route. In the most recent round of Super Bowl ads, medical technology company, Dexcom, combined ethos and logos in a spot for their wearable blood sugar tracking device.

Dexcom got Nick Jonas, a famous pop star who lives with diabetes, to be the spokesperson for the tech. Not only does Jonas lend his star credibility to the ad, he actually has the condition Dexcom’s device claims to help monitor.

The six principles of influence

Now that we’ve covered the three main persuasion strategies in advertising, let’s dig a little deeper.

Ethos, logos, and pathos aren’t the only things that can influence people to buy a product. There are other factors that, when paired with one of the three major methods of persuasion, can be even more effective.

Dr. Robert Cialdini outlines these factors in his book, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. According to Cialdini, there are six of them:

- Reciprocity

- Consistency

- Social Proof

- Authority

- Liking

- Scarcity

Each of these factors is a psychological trigger that can be used to nudge people in a certain direction. We’ll go into each of them in more detail below.

Reciprocity

The rule of reciprocity says that, when someone does you a favor, you feel like you owe them one in return. Advertising plays on that by offering something of value in the hope that people will feel compelled to buy in.

This tactic can take many forms. It could be a popup ad on a clothing website that says “get exclusive deals by signing up now.” It could be a free gift with a purchase, or a coupon offer when you sign up for a mailing list. Here, an enticing reward is offered and the buyer reciprocates with something valuable of their own — like an email address or purchase.

The idea is that both sides benefit upfront, but in the long run it’s the seller who gets the most out of the deal. If a retail store adds someone to their email list, they have that person as a contact until they opt out. If their promotion got someone to buy, odds are they’ll come back.

Consistency

This principle banks on the fact that people look for places consistent with their values when shopping. People are more likely to gravitate to a brand that reflects their self-image. Once we find them, we commit to them.

And if people do that in a public way, like checking in to a restaurant on Facebook, they’re more likely to stick by those choices. It’s also a hassle to find a new place to shop after going through the process of a purchase.

Marketers can take advantage of those principles by encouraging public reviews or check-ins on social media. If you’re using an email marketing platform (and you should be), you can incorporate this principle into the language you use: “It’s been a while, we miss you! Come back and see what’s new.”

Social proof

People are more likely to make a purchase if they see a business recommended by someone they know. The concept of social proof, also called social influence, says that people look to the most popular thing to validate their choices.

As social creatures, people are always looking to one another for cues as to how they should act. Cialdini describes social proof this way in his book:

“Whether the question is what to do with an empty popcorn box in a movie theater, how fast to drive on a certain stretch of highway, or how to eat the chicken at a dinner party, the actions of those around us will be important in defining the answer.”

The numbers seem to back this up. 92 percent of people are more likely to trust unpaid recommendations over other ad types, and 82 percent of Americans say they ask friends and family for recommendations when making a purchase.

You can add social proof elements to your marketing in many subtle ways. Adding the logos of past clients to your website can serve as a testimonial. Little pop-up boxes that say “Jane in Wisconsin just bought 1 handmade leather bracelet,” signals that people want that product.

Even expressions like “bestseller” and “enjoyed by 9,000 happy customers and counting” are a form of social proof. It feels like that many people can’t be wrong.

Providing incentives for sharing your product can help convince more people to buy. Try giving people a small reward like a coupon for reviewing your business or sharing it on Twitter. If someone sees their friend share something on social media, it’ll hold more weight than a random ad.

Authority

Human beings are raised to respect authority figures and look to them for guidance. That’s why bringing in an expert for a logos-based argument or a trusted celebrity for an ethos-based one is so effective.

When deciding whether to make a big purchase, people still look to those figures for an example. Better still if they can buy a product directly from someone seen as an expert.

That’s one reason influencer marketing has become so popular. People trust popular social media figures and can feel close to them. If someone’s favorite Instagram makeup guru recommends a product, they’re probably more likely to buy it, especially if the influencer’s values are aligned with theirs.

Cosmetic products use this tactic a lot. Ads will say “9 out of 10 dentists recommend this toothpaste,” or “dermatologist-developed face wash.” That language says that the experts green-lit this product, so you don’t have to worry.

Liking (or likability)

This one’s pretty simple: people are more likely to buy from someone they see as likable. Friendly salespeople are more enjoyable to talk to than rude ones and leave the customer with a better overall feeling about their experience.

This tactic can also be used to make the customer feel better about themselves. Paying them compliments can make them feel liked and view a company more favorably.

If you’ve ever seen a sign that says “our friendly staff is here to answer any questions you have” or gotten an email with a subject line like “join other successful professionals like you at our online conference,” you’ve seen this tactic at work.

Scarcity

Scarcity is the idea that there’s only a limited amount of something to go around. Marketers use this tactic all the time to hype up a limited-run product, outlining how amazing it is and telling people they’d better hurry to get it now before it’s gone for good.

Creating scarcity around a product also creates a sense of urgency. There’s an invisible ticking clock, a deadline the buyer has to meet before they can’t get that product anymore. Scarcity is, as you might’ve guessed, a very pathos-based appeal.

Etsy is particularly good at this. If you’re looking at a product, the site will tell you how many people already have it in their cart, and how many are left. Ebay will tell you how many people are watching a product, and there’s usually a clock ticking down the minutes until that listing expires.

The clothing brand Cloak has mastered the art of scarcity, only offering a limited run of themed items with each release. By the time you see an ad for the latest collection, it’s usually almost sold out.

Putting it all together

Persuading people to buy your product in a sea of other businesses isn’t easy. But with these tips, it could be a little easier next time you run a campaign.

It’s a good idea to see which of the three major persuasive techniques in advertising would best suit your product, and go from there. Selling men’s soap? It might be best to go with a pathos approach skewed toward humor like Dr. Squatch.

You don’t have to stick to just one persuasive element. If it works, incorporate two. Have an expert spokesperson extoll the values of your product or a qualified doctor state the benefits.

Plus, building in other elements of influence will do even more to help your argument. For example, creating a sense of scarcity around your product with limited runs or limited time offers creates a sense of urgency, while including social proof elements like reviews establishes credibility.

Whether it’s humor, hard facts, or emotional storytelling, experiment with different elements of persuasion and see what works best for your brand.

For more marketing insights, like how to keep your emails from landing in the spam folder, head over to the Constant Contact blog and check out our marketing guide, The Download.